Richard Barber examines recently unearthed sources to construct a convincing scenario of Edward III’s inspired victory over the French in 1346.

Edward III and the Battle of Crécy | History Today The Battle of Crécy in an illumination from 'Les Chroniques de France', c.1350The Genoese crossbowmen halted at the foot of the slope. It had been a long hot day, marching to encounter the English army, which at last was in sight. Giovanni could see a group of men on the hill and to his surprise they were all dismounted. He had expected a mounted army, small perhaps, but very like the French troops coming up behind him, with their splendid steeds and banners. Instead there were rows of men, whose armour did not show whether they were knights or not and whose shields he could not make out at a distance. On either side of the group there were carts, as so often on a battlefield, and he assumed these were simply parked as a rough barrier to prevent an attack from the flank. An easy job, he thought, and it should soon be over, with some booty to take home, particularly as the English had been in the field for weeks and were said to be short of supplies.

The Battle of Crécy in an illumination from 'Les Chroniques de France', c.1350The Genoese crossbowmen halted at the foot of the slope. It had been a long hot day, marching to encounter the English army, which at last was in sight. Giovanni could see a group of men on the hill and to his surprise they were all dismounted. He had expected a mounted army, small perhaps, but very like the French troops coming up behind him, with their splendid steeds and banners. Instead there were rows of men, whose armour did not show whether they were knights or not and whose shields he could not make out at a distance. On either side of the group there were carts, as so often on a battlefield, and he assumed these were simply parked as a rough barrier to prevent an attack from the flank. An easy job, he thought, and it should soon be over, with some booty to take home, particularly as the English had been in the field for weeks and were said to be short of supplies.

The order was given to move forward. The ground was wet from a recent shower and men slipped and stumbled on the chalk, but they went on confidently, knowing that their weapons were the most powerful on the battlefield. Knights feared and disliked the crossbow, but could not do without them: they could break up a defensive formation with their deadly fire, leaving the enemy at the mercy of a cavalry charge.

As the crossbowmen closed on the English, they halted to draw their weapons: with the point of the bow on the ground they put their foot in a kind of stirrup to steady it as they wound the string back to give a massive tension before loading the bolt. But the slipperiness of the ground betrayed them and it was some minutes before they could resume their march. To reload again was going to be very difficult, thought Giovanni.

They were a hundred yards or more short of the range at which they could attack the enemy. They could now see that the carts were not simply on the flanks, but formed a great horseshoe round the whole army, with two wings that came out so that the attackers would be funnelled into a narrow opening. The nearest carts were covered, which surprised Giovanni, but as he puzzled over this the covers were thrown back. Archers using bows of a kind he had never seen before, like large hunting bows, stood up on the carts and began to fire. A hail of arrows, deadly at a much longer range than that of the crossbows, began to fall. The crossbowmen fired back, only to see their bolts fall short. They reloaded, slipping on the chalk again, but the English arrows were finding their mark and the archers could keep up an almost continuous attack. Giovanni turned and fled, only to find that the French behind him, furious at the failure of the Genoese, were shouting ‘Traitors!’ and trying to force them to retreat. Somehow he escaped and when he turned to look back he saw the French cavalry mown down in the trap that the English had set, their horses terrified by strange explosions, which he had never heard before. Later he learnt that these were from the first guns to be used on a battlefield in Europe.

Eyewitness accounts

This account may read like fiction, but it is based on an extraordinary discovery: a long description of the 1346 Battle of Crécy, written in Rome within ten years of the event, which appears to draw on the experiences of one of the Genoese crossbowmen at Crécy and also on a report on the battle given by a knight in the retinue of King John of Bohemia. Italian merchants maintained a network of correspondents throughout Europe and an eyewitness report of the battle would have been important political news for their business. This was probably the route by which the crossbowman’s experiences found their way back to Italy and they were used by the anonymous author of the chronicle. Even more surprisingly, this account was ignored by historians until five years ago.

Edward III’s victory over the formidable French army at Crécy in 1346 shocked Europe. The French had suffered serious defeats before, as in the Battle of the Golden Spurs against the Flemish at Courtrai in July 1302, and had in turn inflicted a similar defeat on the Flemish at Cassel in 1328. These were both battles of cavalry against infantry, with a mounted army of French knights attacking the pikemen of the Flemish towns, and the tactics were relatively orthodox. Crécy was a contest between two armies, which, on the face of it, were of similar composition: knights supported by infantry. The English had no particular reputation as formidable fighters: their victory over the Scots at Halidon Hill in 1333 was seen as a minor affair and scarcely reported outside the British Isles. The size of the armies was very uneven, with the English severely outnumbered. The English archers had never been involved in a major battle on the Continent before and the slaughter they inflicted on the French nobles was a major sensation.

Yet there is more to Crécy than the use of a new secret weapon. The tactics on the battlefield, particularly the disposition of the archers, have been the subject of endless debate. John Keegan’s The Face of Battle (1976), the classic modern account of the difficulty of determining what happens in the course of a battle, is echoed in the chronicle of Gilles le Muisit, abbot of St Martin at Tournai, writing about the battle five years after the event:

The events of war are uncertain: the conflict is between deadly enemies, with each fighting man intent on conquering rather than being conquered. No one can take account of all those fighting around him, nor can those present form a good judgement of these matters. Only the result of their deeds can be judged. Many men say and record many things about this conflict. On the side of the French king and his men some maintain things that cannot be known for certain. Others, on the part of the English king, also maintain things about which the truth is not known. Because of these disparate opinions I will not enquire after the event about what cannot be proved. Instead I have tried to satisfy the understanding of those who come after me by setting down only those things which I have heard from certain people worthy of belief, even if I cannot be totally sure that they are what happened.

What really happened?

If we are to discover ‘what really happened’ we have to look first at who might have been able to observe the events in more general terms and also at whether there were fixed details, such as the position taken up by the English, which can be found in the comments of a number of witnesses. In terms of the action we can say no more than that the French onslaught seems to have been disordered and impetuous and, therefore, no French witness is likely to have been able to form ‘a good judgment’ of what took place. On the English side, Edward and his commanders would have known exactly how they had drawn up their troops: but the king’s report home about the battle tells us almost nothing, except that there was ‘a small area’ where most of the slaughter took place. The only other people who would have seen the English array clearly and at relatively close range were the Genoese crossbowmen, who advanced confidently, certain that their deadly weapons would rapidly dispatch the dismounted English knights and their infantry.

The anonymous Roman chronicle, where the new account is to be found, is famous for its dramatic account of the republican politics of Rome in the 1350s; the information on Crécy was not of great interest to the Italian historians, who originally edited it. It is a difficult text to analyse. Written by a well-educated author, it is in a broad Roman dialect, but has many aspects of popular oral literature, particularly the repetition of key phrases in the manner of a ballad singer. The content, however, is another matter. The striking aspect of this account is that it is in parts very detailed in a way that would be difficult to invent. To take a single instance: the attack by the crossbowmen failed and another Italian chronicler attributes this to the crossbow strings being wet. He is right about the battle being fought in showery weather, but the Roman chronicle tells us that the rain had made the ground so slippery that the crossbowmen could not draw their bows, because, when they put their foot in the stirrup that had to be planted firmly on the ground so that the string could be wound upwards and tensioned, it was impossible to hold the bow still.

The land at Crécy is chalk, with a thin covering of topsoil and, like all chalk hills, is ‘slick as silk’ after rain. Other aspects of the Roman account are wildly off the mark, but these concern matters which a member of the army would only have known by hearsay. I believe this is one of those moments when, for once, we can actually ‘see’ the reality of medieval battle: a man at arms struggling with his weapon in adverse conditions.

If this is the case, then we need to pay close attention to what the chronicle has to tell us. Until now the battle has largely been described in terms of a chivalric encounter, Edward’s advantage being his use of the archers who had proved so effective in the Scottish wars ten years earlier. The disposition of the archers has been the subject of endless debate and it is only by looking carefully at what the sources say that we can discover the surprising truth. Edward fought the battle from within a fortified laager of carts, a fact that is confirmed by many of the other chroniclers but which has been ignored until now because it did not correspond with the accepted image of chivalric warfare. Indeed, the cart was a notoriously shameful object in chivalric literature: knights were taken in carts to meet their end if they had been condemned to death; Lancelot was held to have been shamed by stepping into a cart in order to rescue Guinevere when his horse had been killed; and Philip VI of France shamed the earls of Salisbury and Suffolk by taking them in a cart to Paris when they were captured near Lille in 1340.

The anonymous Roman chronicler tells us that Edward watched them and knew for certain that he could not escape giving battle:

Considering the number of the French it is not surprising that he was a little afraid. He was doubtful and said aloud: ‘God help me!’ Then, quickly, he surrounded his host with strong iron chains and a number of iron stakes stuck in the ground. This surround was made in the shape of a horseshoe, closed all round except for a larger space behind, like a gateway for the entrance and exit. Then he had deep ditches dug where there were weak points. All the English were set to work. Then this chain was surrounded by carts which they had brought with them. They put one cart beside the next with the shafts up in the air. It looked very like a walled city, with the carts stood in a row.

Then the king arranged his troops. On the left flank, on the side towards Crécy, there was a little hill. On this was a piece of woodland. The corn was also standing, which had not been harvested. It was September and because it had been very cold, the corn had only just ripened. In the wood and in the cornfield he arranged 10,000 English archers in hiding. Then he placed a barrel of arrows in each cart. He allocated two archers to each barrel. He selected 500 well-equipped horsemen, whose captain was Edward, Prince of Wales, his son. This was the first battalion. Behind them he placed two wings each of 500 knights, one on the right and one on the left. A further 1,000 knights were placed behind them, who were the third battalion. He placed himself at the rear with all the other knights, behind the host and behind the chains. When he had done this he comforted his men and commended himself to God and said: ‘Oh God, defend and help the righteous cause!’ Thus he set out his army, which made a fine array. It was Saturday, September 3rd.

The most reliable account of the tactics of the English battle formation is probably that of Giovanni Villani, the great Florentine chronicler, who undoubtedly used contemporary letters of bankers from Florence as his source. According to him the English defences were centred on a formation of carts and what follows is a reconstruction based on his description.

Reconstructing the battle

First, in the open chalk country of Crécy such an artificial defensive structure would be valuable. The only natural defences mentioned by the chroniclers are a wood on the left flank and hedges. The northern French countryside was different from the terrain of battles such as Halidon Hill, Morlaix (1342) and Poitiers, where formations were determined by the substantial presence of woods and hedges. The contours of the landscape do present some features which were potentially useful. It is reasonably probable that Edward’s position was above the modern village of Crécy, on the ridge which overlooks the valley of the River Maye; and he may well have placed his men so that the one obstacle on this hillside, the steep 16ft-high bank of the Vallée des Clercs, forced the French to attack from a particular direction. No attacking army could cross this obstacle at speed.

In such circumstances Villani’s declaration that ‘they enclosed the army with carts, of which they had plenty, both of their own and from the country’ and his description of the creation of an artificial fortress of carts rings true. The formation would probably have faced more or less due south, at the head of one of the valleys that run up to the ridge from the river. The carts were probably drawn up in a roughly circular formation and may have been two or more deep, chained wheel to wheel judging from the evidence from the battle of Mons-en-Pévèle in 1304 and from the Hussite Wars fought in Bohemia in the 15th century.

Use of carts to provide a fortified encampment to protect the baggage is widely attested in the 13th and 14th centuries and Philip Preston has suggested that the practice of surrounding the army with carts might also have been used when encamping for the night. Certainly there were men with the army who were practised in manoeuvring the four-wheeled carts into an array of some kind and Edward had arrived at the battlefield two days before. He had more than enough time to ride over the ground, select a suitable position and organise the arrangement of the carts. Furthermore, the evidence points to the availability of enough carts to create such a circle. The anonymous Roman chronicler’s assertion that Edward brought 3,000 carts with him on the expedition is definitely too high. As a working figure let us take a recent estimate of a ratio of carts to men of 1:20, giving 700 carts for an army of 14,000 men.

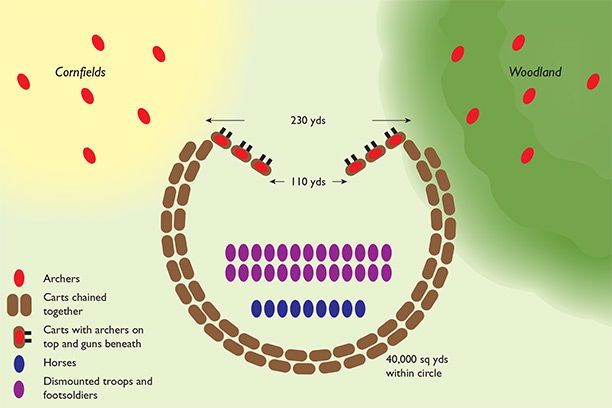

The probable length of each cart when drawn up in formation would be not less than six feet. They were positioned lengthways around the perimeter, with the shafts raised to close the gaps that would otherwise be left between the carts. If the carts were arranged in a double row, this would give a ring 700 yards in circumference, to which we have to add the gap of 100 yards at the entrance. This gives an enclosed area of about 20,000 square yards. The historian Andrew Ayton estimates the total army at around 2,800 men-at-arms, 3,000 mounted archers and 8,000 infantry – about 14,000 men in all. The archers were deployed on the carts, or outside on the wings. Also within the ring were the horses for the men at arms, giving a total of about 11,000 men and 3,000 horses. The only available calculation for the space occupied by a medieval army drawn up in battle formation is for the Swiss army at the battle of Morat in 1476, where 10,000 men are thought to have occupied an area of 3,600 square yards. If we allow an increased space of half a square yard for each man and an estimated two square yards for each horse, this gives a total of 11,500 square yards, leaving adequate room for formation and manoeuvre. These are of necessity theoretical calculations, but they indicate that there is nothing impossible about the idea of the cart fortification with the bulk of the English army inside it. The entrance of 100 yards or less, while open enough to invite the enemy to attempt an attack, would be a death trap, given the covering fire from the archers on the carts. The carts were probably not in an exact square, but in a diamond or circle to provide a better forward line of fire for the archers. The diagram below is a suggestion as to how this might have worked.

Villani makes it clear that there was a substantial opening in the array, sufficient to allow the passage of numbers of men at arms; equally, this opening created ‘a narrow place’. This imitated artificially a feature found at Halidon Hill, and to a lesser extent at Morlaix and Poitiers, a valley which acted as a narrowing funnel, compressing the attacking force into a front which meant that they could not maintain their formation. Nor were superior numbers a striking advantage under such conditions, as only a relatively small number of men would be engaged at any one time.

Edward added the archers to this defensive formation, which restricted the area of action of his most effective long-range weapon. According to the evidence of Villani and the anonymous Roman chronicler, which is supported in general terms by other chronicles, there were two wings of archers outside the circle. These were concealed, one in an unidentified wood and the other in tall standing corn. The distance between these wings, according to the longbow expert Robert Hardy, should have been no greater than 500 yards to give proper covering fire and the suggested size of the array of carts fits well with this calculation. Furthermore, Edward placed archers on the carts. Villani’s evidence on this is detailed and controversial. It would seem that they were concealed and protected by the canvas of the carts, which would have been supported on wooden hoops (as in an illustration from the Luttrell Psalter of an admittedly luxurious royal travelling wagon). These carts were perhaps placed at an angle to the entrance to the array of carts, so that the crossfire would cover the gap to deadly effect; their supplies of arrows were in barrels on the carts, within easy reach. Furthermore – and this is a speculation – if the front row of carts were empty it would be extremely difficult to reach the archers with a lance if a knight did penetrate to the carts themselves. Men on foot would have to clamber up the wheels to get at them. Later Bohemian battle wagons carried ladders for the occupants to get up and down.

The guns were, according to Villani, positioned beneath the carts. They would have been relatively small, probably the mobile cannons called ‘ribalds’, and such a placing would be perfectly possible. They would probably have been better at causing panic among the horses than actually inflicting serious injury, except at a relatively short range. About a hundred were shipped with the expedition, but Edward did not necessarily deploy them all.

Once the archers were in position, and the men at arms drawn up in battle order within the array, the archers would conceal themselves. From the foot of the hill the approaching French would have seen a small army standing in an array of carts, which looked like the traditional method of guarding the rear of a defensive position. The carts would have served to conceal the true numbers within the ring and would have made the English army seem a tempting target.

As soon as the first French forces came within range the archers on the wings would have stood up and begun their deadly volleys. This was what the Genoese crossbowmen encountered. A commander with some control over his troops would have halted the attack to consider how to deal with the archers. Instead, the uncontrolled French cavalry rode over the crossbowmen, wasting their energy on attacking their own men, and into the second trap, the archers concealed at the entrance under the canvas of the carts.

Even so, the sheer mass of the French cavalry enabled them to force their way into the ‘narrow place’, where the Prince of Wales’ men awaited them. It was in this ‘small area’ that, according to Edward himself, the real slaughter took place. The defensive array and the ambush had done their work and the superior numbers of the French army were no longer an advantage. The battle was not won, however. In the struggle that ensued, the discipline and battle experience of the English were the decisive factors. It is possible that the manoeuvre used at Poitiers ten years later, an encircling movement from the rear of the English army to attack the enemy from an unexpected quarter, may have been employed. There would have been time to disengage a couple of dozen carts once it was clear that the main action was at the front of the array, so the existence of the circle would not have prevented such a manoeuvre.

Edward’s majesty

If we are to accept this reconstruction as a possibility, it would mean that the emphasis of Edward’s military thinking went beyond the creation of an army which was well organised and formed of men who had fought together. It extended to the deployment of the latest technology and a genuine understanding of tactics and of the need for a specific type of site in order to make the most effective use of his archers. When he could not find the terrain that he needed, Edward was prepared to create, by artificial means, the necessary obstacles and constraints that would hinder the enemy.

Recent biographies have rescued Edward III from the image of a classic chivalric monarch and from the neglect of his long rule by historians more interested in the political dramas of the reigns of his father and grandson. It seems dangerous to add yet more reasons to regard Edward III as the greatest of all English medieval monarchs, but the picture that this interpretation paints shows him as an innovator and a tactician who responded to a dangerous situation with inspired thinking.

No comments:

Post a Comment