Kurt Vonnegut on the Shapes of Stories and Good News vs. Bad News

by Maria Popova

“The truth is, we know so little about life, we don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is.”

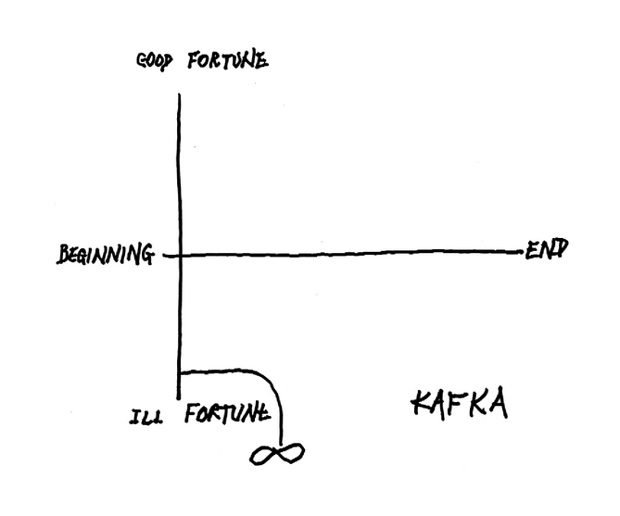

This season has been ripe with Kurt Vonnegutreleases, from the highly anticipated collection of his letters to his first and last works introduced by his daughter, shedding new light on the beloved author both as a complex character and a masterful storyteller. All the recent excitement reminded me of an old favorite, in which Vonnegut maps out the shapes of stories, with equal parts irreverence and perceptive insight, along the “G-I axis” of Good Fortune and Ill Fortune and the “B-E axis” of Beginning and Entropy. The below footage is an excerpt from a longer talk, the transcript of which was published in its entirety in Vonnegut’s almost-memoir A Man Without a Country (public library) under a section titled “Here is a lesson in creative writing,” featuring Vonnegut’s hand-drawn diagrams.

This season has been ripe with Kurt Vonnegutreleases, from the highly anticipated collection of his letters to his first and last works introduced by his daughter, shedding new light on the beloved author both as a complex character and a masterful storyteller. All the recent excitement reminded me of an old favorite, in which Vonnegut maps out the shapes of stories, with equal parts irreverence and perceptive insight, along the “G-I axis” of Good Fortune and Ill Fortune and the “B-E axis” of Beginning and Entropy. The below footage is an excerpt from a longer talk, the transcript of which was published in its entirety in Vonnegut’s almost-memoir A Man Without a Country (public library) under a section titled “Here is a lesson in creative writing,” featuring Vonnegut’s hand-drawn diagrams.

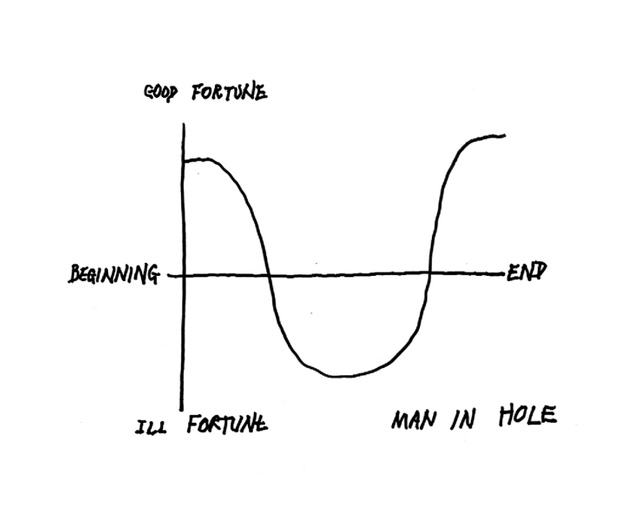

Now let me give you a marketing tip. The people who can afford to buy books and magazines and go to the movies don’t like to hear about people who are poor or sick, so start your story up here [indicates top of the G-I axis]. You will see this story over and over again. People love it, and it is not copyrighted. The story is ‘Man in Hole,’ but the story needn’t be about a man or a hole. It’s: somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again [draws line A]. It is not accidental that the line ends up higher than where it began. This is encouraging to readers.

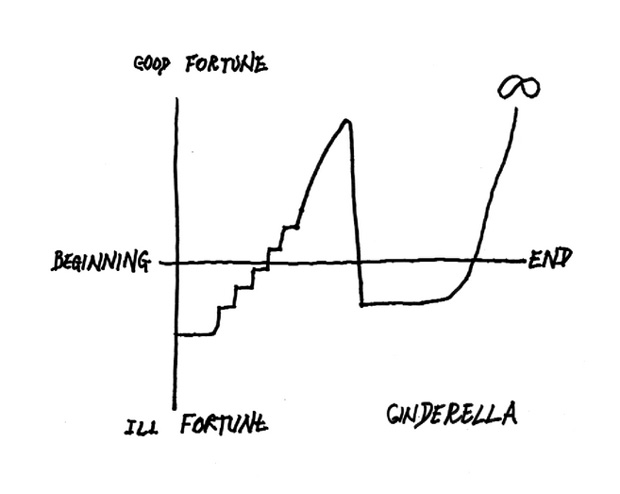

Though the video ends after Cinderella, in A Man Without a Country Vonnegut goes on to sketch out a fourth plot, that of a typical Kafka story:

Now there’s a Franz Kafka story [begins line D toward bottom of G-I axis]. A young man is rather unattractive and not very personable. He has disagreeable relatives and has had a lot of jobs with no chance of promotion. He doesn’t get paid enough to take his girl dancing or to go to the beer hall to have a beer with a friend. One morning he wakes up, it’s time to go to work again, and he has turned into a cockroach [draws line downward and then infinity symbol].It’s a pessimistic story.

He then moves on to Hamlet, delivering his signature blend of literary brilliance and existential philosophy:

The question is, does this system I’ve devised help us in the evaluation of literature? Perhaps a real masterpiece cannot be crucified on a cross of this design. How about Hamlet? It’s a pretty good piece of work I’d say. Is anybody going to argue that it isn’t? I don’t have to draw a new line, because Hamlet’s situation is the same as Cinderella’s, except that the sexes are reversed.

His father has just died. He’s despondent. And right away his mother went and married his uncle, who’s a bastard. So Hamlet is going along on the same level as Cinderella when his friend Horatio comes up to him and says, ‘Hamlet, listen, there’s this thing up in the parapet, I think maybe you’d better talk to it. It’s your dad.’ So Hamlet goes up and talks to this, you know, fairly substantial apparition there. And this thing says, ‘I’m your father, I was murdered, you gotta avenge me, it was your uncle did it, here’s how.’

Well, was this good news or bad news? To this day we don’t know if that ghost was really Hamlet’s father. If you have messed around with Ouija boards, you know there are malicious spirits floating around, liable to tell you anything, and you shouldn’t believe them. Madame Blavatsky, who knew more about the spirit world than anybody else, said you are a fool to take any apparition seriously, because they are often malicious and they are frequently the souls of people who were murdered, were suicides, or were terribly cheated in life in one way or another, and they are out for revenge.

So we don’t know whether this thing was really Hamlet’s father or if it was good news or bad news. And neither does Hamlet. But he says okay, I got a way to check this out. I’ll hire actors to act out the way the ghost said my father was murdered by my uncle, and I’ll put on this show and see what my uncle makes of it. So he puts on this show. And it’s not like Perry Mason. His uncle doesn’t go crazy and say, ‘I-I-you got me, you got me, I did it, I did it.’ It flops. Neither good news nor bad news. After this flop Hamlet ends up talking with his mother when the drapes move, so he thinks his uncle is back there and he says, ‘All right, I am so sick of being so damn indecisive,’ and he sticks his rapier through the drapery. Well, who falls out? This windbag, Polonius. This Rush Limbaugh. And Shakespeare regards him as a fool and quite disposable.

You know, dumb parents think that the advice that Polonius gave to his kids when they were going away was what parents should always tell their kids, and it’s the dumbest possible advice, and Shakespeare even thought it was hilarious.

‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be.’ But what else is life but endless lending and borrowing, give and take?

‘This above all, to thine own self be true.’ Be an egomaniac!

Neither good news nor bad news. Hamlet didn’t get arrested. He’s prince. He can kill anybody he wants. So he goes along, and finally he gets in a duel, and he’s killed. Well, did he go to heaven or did he go to hell? Quite a difference. Cinderella or Kafka’s cockroach? I don’t think Shakespeare believed in a heaven or hell any more than I do. And so we don’t know whether it’s good news or bad news.

I have just demonstrated to you that Shakespeare was as poor a storyteller as any Arapaho.

But there’s a reason we recognize Hamlet as a masterpiece: it’s that Shakespeare told us the truth, and people so rarely tell us the truth in this rise and fall here [indicates blackboard]. The truth is, we know so little about life, we don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is.

And if I die — God forbid — I would like to go to heaven to ask somebody in charge up there, ‘Hey, what was the good news and what was the bad news?’

In the same section of A Man Without a Country, Vonnegut offers a delightfully dogmatic rule of writing:

First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college.

Complement with Vonnegut’s 8 rules for writing stories.

undefined

No comments:

Post a Comment